The Forest Through the Trees

Why I left my CEO job to start this newsletter

I’ve been a struggling startup founder in Silicon Valley for the past 11 years, ever since I took a Stanford class and formed a team with a few Indonesian classmates to build a Blackberry app to solve Jakarta’s massive traffic problem.

Not surprisingly, that idea failed, but I had caught the founder bug. This began a long trek through the wilderness of startup failure.

There was the Wealthfront for family offices idea that went nowhere, the PDF table extraction tool for which my friend Max and I managed to raise a grand total of $240k from our friends and family, and mercifully, an acqui-hire that allowed us to pay them back, which I made sure to frame as a successful exit.

Rather than generational wealth or saving mankind, my reason for persevering was more basic: I couldn’t conceive of myself as a failure. Before coming to Silicon Valley, I had spent 9 years as a trader in the infamous subprime mortgage CDO industry and had grown accustomed to a steady rate of inflation in both title and all-in comp.

While I had left the finance industry because I wanted to create things that were actually valuable, my ego wouldn’t settle for being a product manager at someone else’s company. After every Techcrunch article about other founders raising huge rounds for ideas that seemed obvious in hindsight, I thought why couldn’t I have done that?

During those long years in the wilderness, raising a Series A round seemed like an impossible, magical threshold, after which I could finally look myself in the mirror without a low-level hum of castigation.

Incredibly, with a lot of luck and hard work, it finally happened.

Last year, my startup raised an $8 million Series A round led by Initialized Capital to build an ecosystem around Hummingbot, the open source market making software that we launched in 2019.

More importantly, over the past few years of building Hummingbot, seeing the myriad ways that our community used it, and understanding the value that it provided to them, I finally understood what genuine product-market fit felt like. Instead of chasing vanity success metrics, I discovered in myself a long-dormant, primal drive to invent something new, to build a product that provided people tangible value for the sake of it, to create a public good.

Liquidity is an essential need for anyone who issues a token, and before Hummingbot, their only option was hiring a hedge fund for market making services. By providing a free, open source bot, we had created the only software-powered solution in an industry dominated by human-powered, often dubious, market makers. In addition, we invented a new type of exchange for market makers instead of retail traders, where liquidity seekers could algorithmically distribute rewards to a decentralized community of liquidity providers, rather than just hiring a single one. Today, Hummingbot has become an indispensable DIY liquidity tool for many token issuers, exchanges, and trading firms, as well as thousands of individual traders and developers around the world.

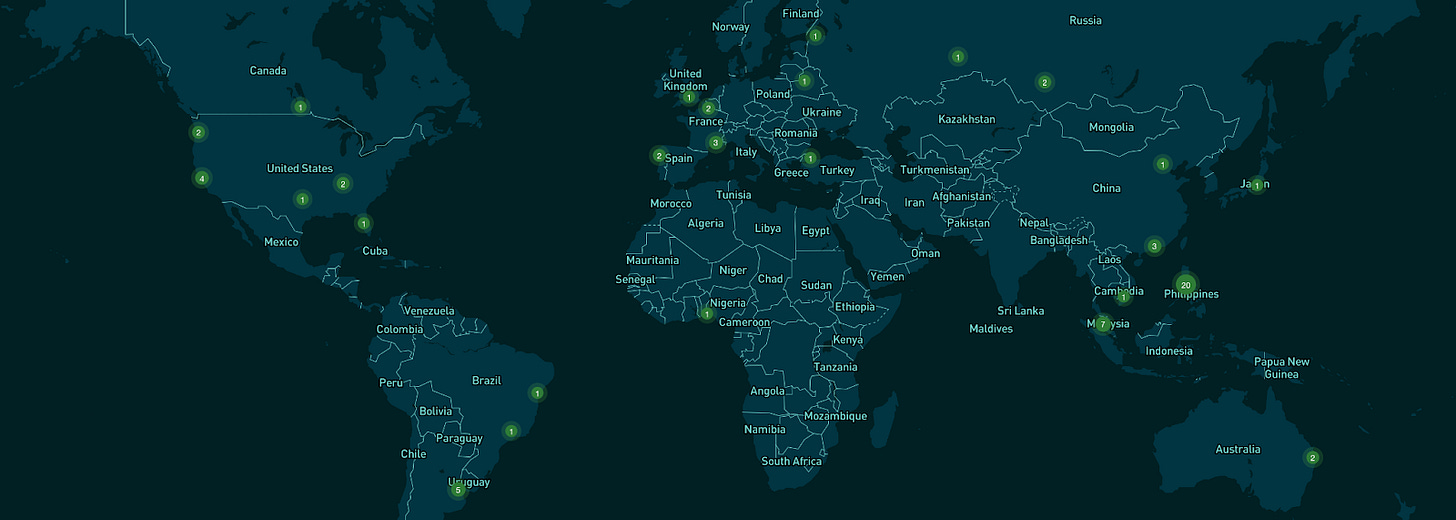

Over the course of 2021, we tripled our team size and spun off the Hummingbot project into a new open source foundation governed by token holders. Entering 2022, I was the CEO of a rapidly growing crypto startup with 70 team members in 20 different countries.

That’s why it took a long time for me to process why I wanted to hand over the CEO job to my co-founder Carlo and embark on a new career as a Substack newsletter writer.

So for this first post, I wanted to tell you my origin story, why I decided to leave my job, and what I’ll be writing about.

I wanted to be a writer when I was young, because I spent most of my time reading books.

My parents worked weekends, so they would drop me off at the local public library, where I spent the entire day curating the set of books that I brought home to read during the ensuing week. Half of the books had to fit precise Dewey Decimal categories (biography, history, science, etc), while I could pick the other half myself, mostly Agatha Christie mysteries and YA fantasy epics that I devoured first.

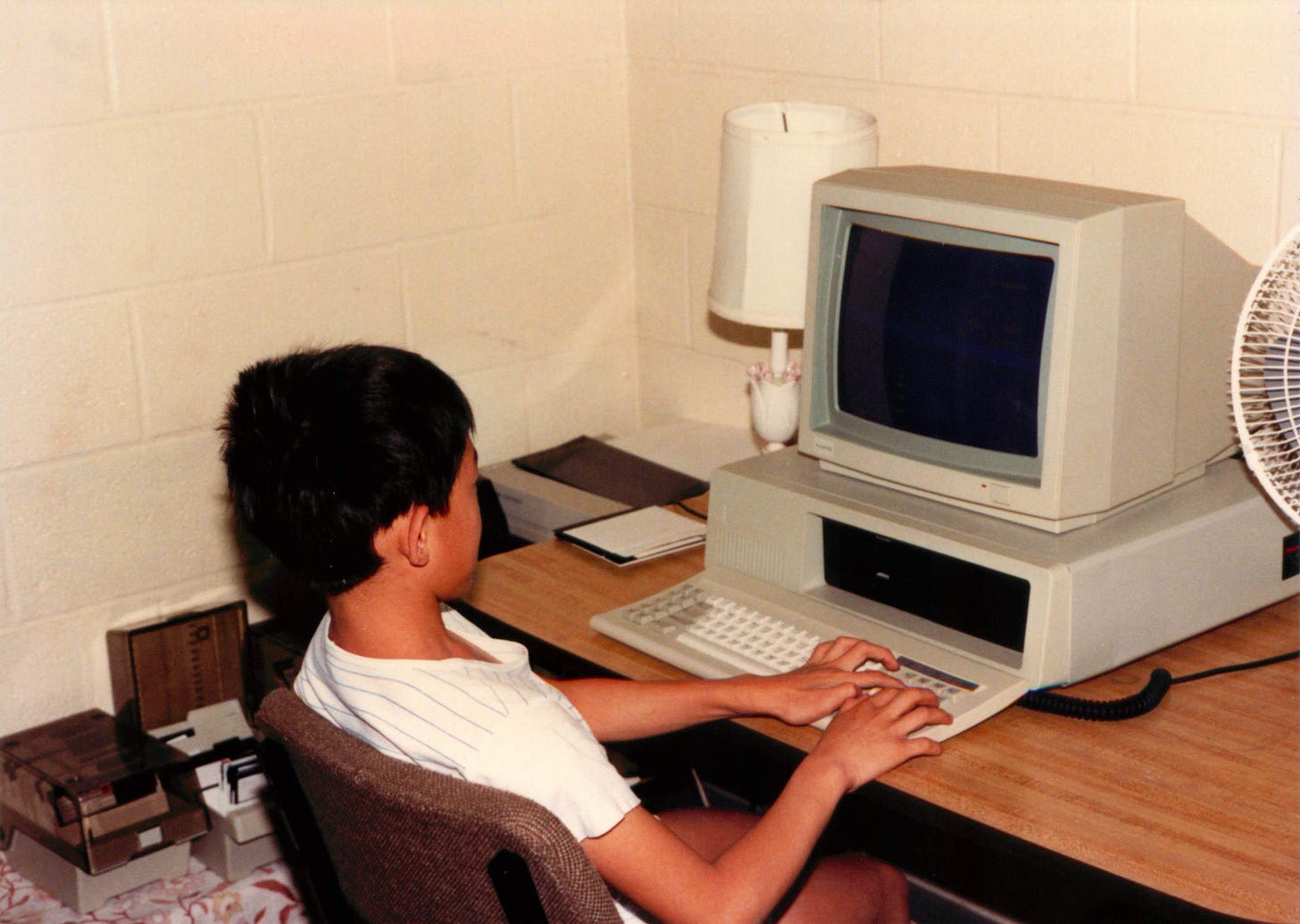

When I wasn’t reading, I was playing computer games like Frogger and Return to Zork on the 386 PC that my parents had the incredible foresight to buy for me in 3rd grade, despite our limited finances back then.

I also spent many nights correcting the grammar in my parents’ cover letters as they looked for jobs. This was a matter of survival for my family. After the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, my dad organized demonstrations at the University of Florida in support of the Chinese student protestors. After getting their PhDs, if my parents couldn’t find employers willing to sponsor their green cards, we might have to go back to China, where, even today, people are disappeared.

Miraculously, after countless rejections, my dad finally landed an internship with a small Philadelphia options trading firm called Susquehanna Investment Group as their first-ever quant hire. SIG grew into one of the largest trading firms in the world, and my dad endured 20 years as one of the few Asians and non-native English speakers on a Wall Street trading floor.

Like many other first-generation immigrants, I learned that getting a good, proper job was the key to success in life. Despite my love for writing (I still treasure my Class of 97 Top English Student plaque), I never seriously considered it as a profession after learning that a journalist’s starting salary was a scant $19k a year.

Instead, I took the diametrically opposite route and went to Wharton undergraduate business school, the finishing school for junior investment bankers and management consultants. There, I met my future Hummingbot co-founder Carlo. We lived in the same freshman dorm and became lifelong friends after discovering a shared enthusiasm for drunken gymnastics.

During university, my favorite books were Liar’s Poker, Michael Lewis’s first book about starting his career on a mortgage trading desk at Salomon Brothers, and the lesser-known but equally-great FIASCO. Where others saw rogue traders who created complex, esoteric products that destabilized markets, I saw inventors who were creating experimental financial products that allocated risk and reward in radical, new ways.

After graduating in 2001, I joined a tiny trading desk at Salomon Smith Barney, the old Salomon Brothers remnants amalgamated with a retail brokerage into a corporate monstrosity sheltered under the drab Citigroup umbrella. My daily work environment was a cavernous Lower Manhattan trading floor, filled with a nonstop cacophony of ringing phones, barking Brooklyn accents, and random pushup contests. None of the mortgage traders, who still answered their phones Salomon Braawthers, knew what we did, only that it involved a lot of fancy computer models.

My desk structured and traded an obscure new product called a collateralized debt obligation (CDO).

As Anthony Bourdain explains above, manufacturing a CDO is similar to alchemy. We transformed a portfolio of high-yield bonds (rated BB and below) into a mix of AAA and other investment grade debt tranches that were sold to banks, pension funds, and insurance companies, along with a harder-to-sell equity tranche aimed at the degenerate investors of the time, family offices and hedge funds.

There was only one problem. CDO market growth was capped by the availability of high-yield bonds in the secondary market. We couldn’t find enough of them to package them into CDOs.

My desk had a potential solution. They wanted to recapture the old Salomon magic and package CDOs using mortgage-backed securities (MBS), especially the subprime variety which had substantially higher yields (ha!) than high-yield bonds. The MBS market was many times larger than the corporate bond market, plus the mortgage trading desk was holding a lot of illiquid inventory that they were eager to offload.

My job was to optimize the deal structure in Excel in order to maximize the yield of the CDO equity tranche, the hardest to sell, while maintaining the necessary ratings on the debt tranches. Tweaking these models (financial engineering) was my favorite part of the job. Each optimization - adjusting the asset composition, building new features into the cash flow waterfall - led to incremental jumps in the equity yield. It was like playing with math legos.

But first, we needed a model. Since a single CDO contained hundreds of MBS, and each MBS contained thousands of individual mortgage loans, using a regular Excel model would be cumbersome and impractically slow. So I built a model like this one that offloaded most of the calculations to VBA and used it to structure South Coast Funding, the first-ever CDO backed by subprime mortgages.

Over the next 7 years, subprime mortgage CDOs became Citigroup’s most lucrative and important fixed income product. The most aggressive buyers, mid-level managers at Asian and Middle Eastern banks and insurance companies, didn’t care what assets were in the portfolio. They were just doing their job, which appeared to be buying the highest yielding bonds of a certain credit rating. Some were so eager to lock in allocations that they would wire us the money before the deal was even officially announced.

Due to insatiable demand from CDOs, the supply of cash MBS in the secondary market ran dry, so we started to package CDOs with synthetic MBS created using credit default swaps, as depicted in The Big Short. Unlike in the Hollywood version, I and my Wall Street counterparts created the initial versions of these instruments. The hard part was convincing hedge funds to short the white-hot US housing market in 2004.

Bizarrely, what should have been the hard part - finding someone to bear the risk associated with a price decline in the US housing markets - was trivially easy, because Citigroup itself wanted to keep the largest tranches in each CDO, which contained embedded liquidity puts:

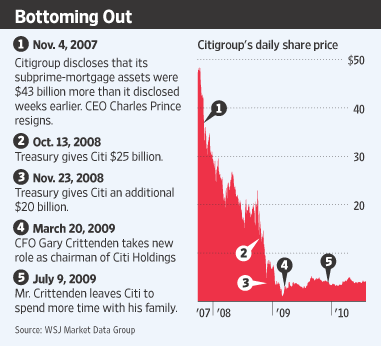

Citigroup almost went out of business in 2008 because it sold products with liquidity puts. That meant that if debt Citi sold to other investors became illiquid, those investors had the right to sell them back to Citi at face value. When debt markets froze, liquidity puts cost Citigroup $25 billion in losses in 90 days, at a time when it had less than $90 billion in equity.

Virtually all Citigroup’s liquidity put losses came from subprime mortgage CDOs that my desk created. Most of them used descendants of my original Excel model.

Believe it or not, this was an independent decision made by Citigroup’s treasury department. In fact, they were eager to hold the super-senior AAA bonds that contained these puts, which had juicy 20-40 bps spreads compared to standard corporate AAA bonds with thin 5-10 bps spreads.

Why? Because the decision makers, mid-level managers from Citigroup treasury, had the same basic job as the foreign CDO buyers: maximizing yield on a bond portfolio while maintaining certain credit rating and duration requirements. Performing too much due diligence might lead to a decision to pass, create more work for everyone on the team, and impact their year-end numbers, while staying silent was much more convenient.

After the bottom fell out in 2008, everyone kept repeating the same stupid cliched phrase: we missed the forest for the trees.

In our continual competition to maximize yields, optimize transactions, and collect the next year-end bonus, we had all missed the perverse incentives that the CDO machine had created.

Not only had this esoteric financial backwater actually warped the US housing market by fueling a bubble that would eventually have to pop, but I felt like I had personally contributed to millions of people losing their jobs and their homes.

Looking for a career reset, I applied to an engineering master’s program at Stanford and, luckily, got in. I had no aspirations to be a founder. I just wanted to leave finance behind.

I’m a very different person today from the lost soul who came to Silicon Valley 11 years ago. Every failed startup idea and VC rejection letter taught me something new - how to build products that solve unmet needs, how to explain ideas to investors in ways they understand, how to manage people, how to understand myself better.

After raising our Series A last year, I spent much of the rest of the year interviewing candidates over Zoom, as we embarked on an ambitious hiring binge. Organizing my calendar became a more depressing version of Tetris as meetings stretched from early morning to late night.

Hummingbot’s core philosophy is that talent exists everywhere. We have built a 70-person team in 20 different countries, including Nigeria, Russia, Malaysia, and Iran. Coordination across time zones and cultures is still a huge ongoing challenge, but we make it work because of a bottoms-up, remote culture, powered by responsible, hard-working individuals who could reliably do their jobs while trusting their colleagues to do theirs.

In my opinion, Hummingbot’s most durable competitive advantage is our ability to scale a highly technical, globally distributed team.

The person responsible for running our organization efficiently is my co-founder and COO Carlo, who honed his finance and operational chops during a 13-year investment banking career at Goldman Sachs and other top Wall Street firms. But Carlo is much more than just an ex-banker; he is also a talented engineer who set up our initial devOps and blockchain infrastructure stack, and he has always done the small things that drive instill company culture, like organizing board game nights and decorating our Gather space.

Meanwhile, there were certain aspects of the CEO job that I enjoyed and excelled at, such as evangelizing Hummingbot and explaining how it compares to traditional market making. But there were other aspects of my job that I merely tolerated or even neglected, such as defining a clear organizational structure and building repeatable company processes.

Unlike my parents, who had to find employment or risk deportation, I have the opportunity to design and define my job, not just accept the one that society defines for me. Moreover, in order to legitimately espouse a culture of trusting your neighbors to do their jobs at Hummingbot, I have an obligation to set an example to my team.

That’s why I’m excited to announce that Carlo will take over as CEO of CoinAlpha, the company behind Hummingbot, effectively immediately.

This will enable Carlo to focus on growing CoinAlpha’s global team and our two lines of business: our Miner decentralized market making platform and the upcoming Hummingbot Prime product, a SaaS for institutional and advanced Hummingbot users that lets users rapidly backtest any Hummingbot strategy against full-resolution historical order book data.

Meanwhile, I will continue to work for CoinAlpha in a newly created job (working title: evangelizer/explainer/researcher). Using this newsletter, I plan to publish posts and host podcasts that explain how the Hummingbot ecosystem works, as well as explore new technical directions for the Hummingbot codebase.

My inspiration for this job is Vitalik Buterin, who plays a critical role in the Ethereum ecosystem without being involved in the day-to-day operations of the Ethereum Foundation. This frees Vitalik up to write two blog posts a month, attend Ethereum core dev meetings, contribute actively to ethereum/research, and evangelize Ethereum on the conference circuit.

More generally, I hope to bridge the prevailing disconnect between the finance and crypto industries by teaching people on both sides how the other side works.

The traditional finance world worries that crypto will be the next subprime crisis, a gigantic Ponzi scheme that makes a few people rich and many others poorer. True, there are many parallels between the insatiable chase for yield by DeFi token projects and investors today and the CDO excesses of yesteryear. But on the other hand, crypto people feel, justifiably, that regulators wield their power indiscriminately without fully understanding the underlying technology.

We’re talking past each other, not seeing the forest through the trees.

This newsletter will make the case that the crypto and finance industries will gradually fuse over the next few years, because they both solve the same core need: liquidity.

I’ll expand my past content related to market making and liquidity (articles, videos, whitepapers) to shed a bright light on that shadowy, opaque industry. I’ll expose the business model of market makers and how they can charge their customers millions per year. I’ll explain why the AMM (or more precisely, Uniswap’s working version of a decentralized one) is one of the most important inventions in the history of finance.

I will write about how everything in finance is about to change.

We now have all the tools we need to manufacture our own financial instruments, and more importantly, make them liquid and tradeable. These tools, all open source and publicly available, include blockchains like Ethereum, exchanges like Uniswap, and bot software like Hummingbot.

Before, we had to hire a middleman to do this job for us, with titles like venture capitalist, investment banker, and market maker.

Not anymore. Now, anyone can create a token, a digital representation of anything, that can be swapped for any other token on unblockable exchanges located anywhere in the world.

Essentially, we all have the power to invent new forms of money.

Just like the Internet disrupted the media and commerce industries 20 years ago, crypto will change every aspect of finance, in ways both good and bad.

How it will all unfold, I frankly have no idea, but I’m excited to explore what the ramifications might be in this newsletter.

Finally, I want to teach founders what Silicon Valley calls product, the art of building something that people want, coupled with the science of getting someone to pay for it.

All those startup failures, interspersed with a few successes, have forced me to be honest with myself and taught me which product directions tend to work and which fail. I think I can use that experience to dispense hard but necessary product advice, not only to those actively building in the crypto or web3 space, but also to all the aspiring crypto founders out there trapped in traditional finance jobs.

Crypto is a technology that allows anyone to create liquid financial instruments, and like all new technologies, it will be used for both good and evil. While there are certainly scammers out there, most crypto founders are trying to do good by building projects that address the many hard problems that exist in the world.

I’m excited to help them succeed.

Subscribed! So excited for your new journey, Mike.

Congrats ! Hope you find love doing your job.